The tech world is in many ways like a large city. While we spend most of our time in a few neighborhoods, it doesn’t really come as a surprise to encounter an old friend or colleague that you haven’t talked to in years, hanging out in your corner café. So I was not surprised to hear that my old friend Antony Brydon had started a new company with a compelling value proposition, called Directly, and that he and his head of marketing, Lynda Radosevich, thought I’d like to learn about it.

Antony Brydon

I met Antony when he was CEO of Visible Path, an innovative social startup, one that was working to build the work graph — through email analysis — in the ‘00s. Visible Path was acquired by Hoovers in 2008. Perhaps they were a bit ahead of the market, but that’s a sign that Brydon & Co are generally ahead of the power curve.

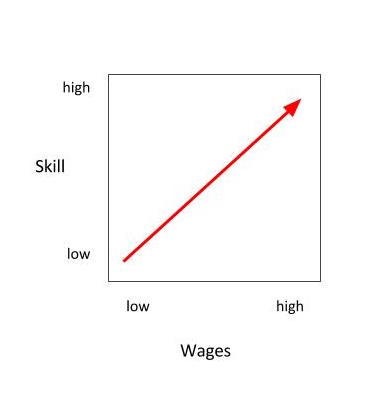

I was also not surprised that Directly’s value proposition is very, very smart: helping other companies scale their customer support capabilities by breaking out of what I think of as the skills versus wages snare (see figure 1).

The snare is this: as the necessary skill level for customer support increases, the wages that must be paid increase. This is a fundamental aspect of supply and demand.

figure 1 — The Skills v Wages Snare

But Antony and his partners have come up with a way to break the snare, and Directly is the platform on which that magic happens.

I recently interviewed Antony about Directly, and why the company is growing so quickly.

The Interview

Stowe Boyd: One thing I’d like you to do is tell the origin story. In every superhero comic strip, there’s the story that they tell about how Peter Parker got bitten by a radioactive spider, or Steve Jobs visiting PARC. So, what led to the founding of Directly?

Antony Brydon: It was not as dramatic as Peter Parker and the radioactive spider, but it was interesting. And it was interesting because the company founding and the initial inspiration were probably 15 years apart. Back before Visible Path, I worked in a call center for a few years: back in ’98. I worked for a venture firm which invested in Genesis, Aspect, and Aurum: a lot of the early call center players.

Call centers was an interesting beat, but it was a little depressing because the customers were very rarely happy with the service they were receiving. – Antony Brydon

For the better part of three years, that was my beat. And I was looking at a lot of Fortune 100 call center buyers to figure out what products they needed. Call centers was an interesting beat, but it was a little depressing because the customers were very rarely happy with the service they were receiving.

The agents in the call center were a downtrodden labor force: modern-day galley ships. The call center managers were doing the best they could, but often saw themselves as sort going to war with the tools they had. Under equipped and underserved. Very tactical.

Genesis had some incredible skill-based routing that I used in a project. It could actually connect a customer to an absolute perfect agent. But that capability wasn’t being used very broadly. There were a lot of reasons it wasn’t. Some of the call centers didn’t want to hire the truly skilled agents because it could cost more money.

SB: Right, and I bet they didn’t want to test people to gather all that data, either. That was expensive, too.

AB: Yes. They didn’t want to break their agents down into different pools based on skills levels because utilization would drop. If you had one homogeneous pool, you could give a call to anybody. If you had 10 skills-based pools, utilization fell through the floor, so the economics fell down. A great example of really great technology that didn’t get applied anywhere near the degree that it should because of the constraints in the business model. And that, entrepreneurially, was pretty depressing to watch.

My diagnosis was that the problem wasn’t the technology. The problem was the talent side of the equation, and how that talent was being managed. There was no amount of technology to fix it. When you’ve had very low skill folks being hired at very low wages, who are being pushed to handle 60, 80, 100 customers a day and sort of being churned out 12, 13 months later once they met the learning curve, well that invariably put a low ceiling on customer experience. A depressing trend, and that was the reason I made a conscientious move to stop working on it

That wasn’t the inspiration for Directly, per se, but that was my diagnosis at the time. That was the real problem. It made me very unexcited.

For the last kind of 15 years, whenever Jeff [Paterson, the co-founder and head of product at Directly] and I sold a company, we would come back to this problem that had bothered me a long time ago and just started hacking to see if we had any new approach or insight that we had that we could bring to bear on it.

SB: You’re saying the obvious thing was being blocked by the business model, which led low-skilled people to become more skilled, and then their higher wages would become unaffordable.

AB: Yes, absolutely. Skilled workers could have been created very quickly. So, if you had a Samsung Galaxy question that was routed to a Samsung Galaxy expert, and that person was doing a normal number of inquiries for the day and wouldn’t have the boot on the back of their neck to get off the phone in 6 minutes. But that was blocked by the economics of the business model, and that blocked the talent model.

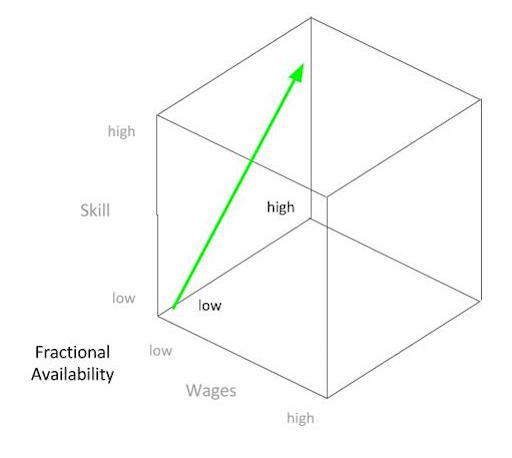

We looked at this in 2001 after eMusic had just got acquired. We looked at it in 2008 after we sold Visible Path. When we came back to it in 2011, we had the benefit of seeing a lot of these on-demand companies coming up. We saw Lyft coming up. And Uber coming up. And Airbnb. And all of these companies taking advantage of a kind of fractional availability.

When we applied that to the old problem, we saw for the first time we saw the potential of pulling together people with much higher skill sets than would ever sit in a call center. And then making them available for small fractions of time. When their skill set really matched a customer’s problem, and at levels where they could really opt in and delight a customer. With that combination of the ability to get more talent than had existed before, and then also to render that talent. Making the business model, the economics of it, work.

So that was the initial insight. That’s what started down that pathway quickly, building some quick primitive apps and starting testing that idea. It bore out very quickly.

We did some initial tests in kind of 6, 12 weeks of initial building. We got some very good signals back that we could attract very skilled folks and pair them with customers very efficiently and very quickly. It took a lot of work to actually develop the engines and all of the enterprise innovations. But those are the book ends. There was that insight in ’98 that no amount technology could fix broken talent model and a broken business model. Then there was that ‘aha’ in 2011 and 2012 that the on-demand piece would be a very elegant solution to this problem.

At that point in the interview, I started to sketch a 3D model in my journal, based on Antony’s use of the term ‘Fractional Availability’. In figure 1, the 2D model above, we saw the snare, the dead-end that Antony has described as an economic problem that technology couldn’t fix in 1998. But with the surge of interest in on demand platforms — like Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb — a new alternative appears.

An additional dimension appears, so that people with high skills can still be affordable, because they don’t have to be hired as full-time workers sitting in a call center. They can be paid only for the time that they are handling customer support requests, and they have gained their expertise at no expense to the company using their services on a part-time, on-demand basis. They’ve gained that skill as a power user, on their own time, for their own reasons.

Figure 2 — Fractional Availability

Here we see the 3D reality: it is possible to pay low ‘wages’ (perhaps ‘costs’ would be better) for highly-skilled customer support because of the wormhole that is fractional availability. (I think of it as something like the Guild Navigators in the Dune series, who can ‘fold space’ and travel ‘without moving’ from one star system to another light years away.)

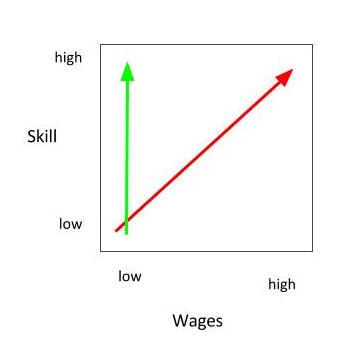

So, if you take the 3D chart above and look at it end on — concealing the dimension of fractional availability, it would look like figure 3, below. Directly allows companies to shift the needle from high costs for high skills, by tapping into the game-changing economics of fractional availability.

Figure 3 — Back in Two Dimensions

Theories into Practice

In the next post in this series, I will dig into the specifics of how Directly has moved the needle at a specific customer’s call center operations, a case study based on the adoption of Directly at MobileIron. But behind that practical and tactical step-by-step adoption is the origin story of Antony’s frustration with call center economics in 1998, and the role that fractional availability is having on the world. Directly’s success has come from harnessing that theory, and making it do the heavy lifting.

Also, you might like to hear Antony and Jonathan Keane,

Director of Customer Service at Republic Wireless in a livecast on the topic: How To Deliver 2.9 Minute Response Times During A New Product Launch, Thursday, February 25 @ 11:00am PST/ 2:00pm EST.

Directly has sponsored this post, but the opinions are my own and don’t necessarily represent Directly’s positions or strategies.